More than 55 million Americans –18% of our population–have disabilities, and they, like all Americans, participate in a variety of programs, services, and activities provided by their State and local governments. This includes many people who became disabled while serving in the military. And, by the year 2030, approximately 71.5 million baby boomers will be over age 65 and will need services and surroundings that meet their age-related physical needs.

Read this to get specific guidance about this topic.

People with disabilities have too often been excluded from participating in basic civic activities like using the public transportation system, serving on a jury, voting, seeking refuge at an emergency shelter, or simply attending a high school sports event with family and friends. The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) is a Federal civil rights law that prohibits discrimination against people with disabilities. Under this law, people with disabilities are entitled to all of the rights, privileges, advantages, and opportunities that others have when participating in civic activities.

The Department of Justice revised its regulations implementing the ADA in September 2010. The new rules clarify issues that arose over the previous 20 years and contain new requirements, including the 2010 ADA Standards for Accessible Design (2010 Standards). This document provides general guidance to assist State and local governments in understanding and complying with the ADA’s requirements. For more comprehensive information about specific requirements, government officials can consult the regulation, the 2010 Standards, and the Department’s technical assistance publications .

The ADA protects the rights of people who have a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits their ability to perform one or more major life activities, such as breathing, walking, reading, thinking, seeing, hearing, or working. It does not apply to people whose impairment is unsubstantial, such as someone who is slightly nearsighted or someone who is mildly allergic to pollen. However, it does apply to people whose disability is substantial but can be moderated or mitigated, such as someone with diabetes that can normally be controlled with medication or someone who uses leg braces to walk, as well as to people who are temporarily substantially limited in their ability to perform a major life activity. The ADA also applies to people who have a record of having a substantial impairment (e.g., a person with cancer that is in remission) or are regarded as having such an impairment (e.g., a person who has scars from a severe burn).

Title II of the ADA applies to all State and local governments and all departments, agencies, special purpose districts, and other instrumentalities of State or local government (“public entities”). It applies to all programs, services, or activities of public entities, from adoption services to zoning regulation. Title II entities that contract with other entities to provide public services (such as non-profit organizations that operate drug treatment programs or convenience stores that sell state lottery tickets) also have an obligation to ensure that their contractors do not discriminate against people with disabilities.

Equal treatment is a fundamental purpose of the ADA. People with disabilities must not be treated in a different or inferior manner. For example:

The integration of people with disabilities into the mainstream of American life is a fundamental purpose of the ADA. Historically, public entities provided separate programs for people with disabilities and denied them the right to participate in the programs provided to everyone else. The ADA prohibits public entities from isolating, separating, or denying people with disabilities the opportunity to participate in the programs that are offered to others. Programs, activities, and services must be provided to people with disabilities in integrated settings. The ADA neither requires nor prohibits programs specifically for people with disabilities. But, when a public entity offers a special program as an alternative, individuals with disabilities have the right to choose whether to participate in the special program or in the regular program. For example:

People with disabilities have to meet the essential eligibility requirements, such as age, income, or educational background, needed to participate in a public program, service, or activity, just like everyone else. The ADA does not entitle them to waivers, exceptions, or preferential treatment. However, a public entity may not impose eligibility criteria that screen out or tend to screen out individuals with disabilities unless the criteria are necessary for the provision of the service, program, or activity being offered. For example:

Rules that are necessary for safe operation of a program, service, or activity are allowed, but they must be based on a current, objective assessment of the actual risk, not on assumptions, stereotypes, or generalizations about people who have disabilities. For example:

There are two exceptions to these general principles.

In some cases, “equal” (identical) treatment is not enough. As explained in the next few sections, the ADA also requires public entities to make certain accommodations in order for people with disabilities to have a fair and equal opportunity to participate in civic programs and activities.

Many routine policies, practices, and procedures are adopted by public entities without thinking about how they might affect people with disabilities. Sometimes a practice that seems neutral makes it difficult or impossible for a person with a disability to participate. In these cases, the ADA requires public entities to make “reasonable modifications” in their usual ways of doing things when necessary to accommodate people who have disabilities. For example:

Only “reasonable” modifications are required. When only one staff person is on duty, it may or may not be possible to accommodate a person with a disability at that particular time. The staff person should assess whether he or she can provide the assistance that is needed without jeopardizing the safe operation of the public program or service. Any modification that would result in a “fundamental alteration” – a change in the essential nature of the entity’s programs or services – is not required. For example:

Under the ADA, a service animal is defined as a dog that has been individually trained to do work or perform tasks for an individual with a disability. The task(s) performed by the dog must be directly related to the person’s disability. For example, many people who are blind or have low vision use dogs to guide and assist them with orientation. Many individuals who are deaf use dogs to alert them to sounds. People with mobility disabilities often use dogs to pull their wheelchairs or retrieve items. People with epilepsy may use a dog to warn them of an imminent seizure, and individuals with psychiatric disabilities may use a dog to remind them to take medication. Dogs can also be trained to detect the onset of a seizure or panic attack and to help the person avoid the attack or be safe during the attack. Under the ADA, “comfort,” “therapy,” or “emotional support” animals do not meet the definition of a service animal because they have not been trained to do work or perform a specific task related to a person’s disability.

Allowing service animals into a “no pet” facility is a common type of reasonable modification necessary to accommodate people who have disabilities. Service animals must be allowed in all areas of a facility where the public is allowed except where the dog’s presence would create a legitimate safety risk (e.g., compromise a sterile environment such as a burn treatment unit) or would fundamentally alter the nature of a public entity’s services (e.g., allowing a service animal into areas of a zoo where animals that are natural predators or prey of dogs are displayed and the dog’s presence would be disruptive). The ADA does not override public health rules that prohibit dogs in swimming pools, but they must be permitted everywhere else.

The ADA does not require service animals to be certified, licensed, or registered as a service animal.

Nor are they required to wear service animal vests or patches, or to use a specific type of harness. There are individuals and organizations that sell service animal certification or registration documents to the public. The Department of Justice does not recognize these as proof that the dog is a service animal under the ADA.

The ADA requires that service animals be under the control of the handler at all times and be harnessed, leashed, or tethered, unless these devices interfere with the service animal’s work or the individual’s disability prevents him from using these devices. Individuals who cannot use such devices must maintain control of the animal through voice, signal, or other effective controls.

Public entities may exclude service animals only if 1) the dog is out of control and the handler cannot or does not regain control; or 2) the dog is not housebroken. If a service animal is excluded, the individual must be allowed to enter the facility without the service animal.

Public entities may not require documentation, such as proof that the animal has been certified, trained, or licensed as a service animal, as a condition for entry. In situations where it is not apparent that the dog is a service animal, a public entity may ask only two questions: 1) is the animal required because of a disability? and 2) what work or task has the dog been trained to perform? Public entities may not ask about the nature or extent of an individual’s disability.

The ADA does not restrict the breeds of dogs that may be used as service animals. Therefore, a town ordinance that prohibits certain breeds must be modified to allow a person with a disability to use a service animal of a prohibited breed, unless the dog’s presence poses a direct threat to the health or safety of others. Public entities have the right to determine, on a case-by-case basis, whether use of a particular service animal poses a direct threat, based on that animal’s actual behavior or history; they may not, however, exclude a service animal based solely on fears or generalizations about how an animal or particular breed might behave.

Allowing mobility devices into a facility is another type of “reasonable modification” necessary to accommodate people who have disabilities.

People with mobility, circulatory, or respiratory disabilities use a variety of devices for mobility. Some use walkers, canes, crutches, or braces while others use manual or power wheelchairs or electric scooters, all of which are primarily designed for use by people with disabilities. Public entities must allow people with disabilities who use these devices into all areas where the public is allowed to go.

Advances in technology have given rise to new power-driven devices that are not necessarily designed specifically for people with disabilities, but are being used by some people with disabilities for mobility. The term “other power-driven mobility devices” is used in the ADA regulations to refer to any mobility device powered by batteries, fuel, or other engines, whether or not they are designed primarily for use by individuals with mobility disabilities, for the purpose of locomotion. Such devices include Segways®, golf cars, and other devices designed to operate in non-pedestrian areas. Public entities must allow individuals with disabilities who use these devices into all areas where the public is allowed to go, unless the entity can demonstrate that the particular type of device cannot be accommodated because of legitimate safety requirements. Such safety requirements must be based on actual risks, not on speculation or stereotypes about a particular class of devices or how individuals will operate them.

Public entities must consider these factors in determining whether to permit other power-driven mobility devices on their premises:

Using these assessment factors, a public entity may decide, for example, that it can allow devices like Segways® in a facility, but cannot allow the use of golf cars, because the facility’s corridors or aisles are not wide enough to accommodate these vehicles. It is likely that many entities will allow the use of Segways® generally, although some may determine that it is necessary to restrict their use during certain hours or particular days when pedestrian traffic is particularly dense. It is also likely that public entities will prohibit the use of combustion-powered devices from all indoor facilities and perhaps some outdoor facilities. Entities are encouraged to develop written policies specifying which power-driven mobility devices will be permitted and where and when they can be used. These policies should be communicated clearly to the public.

Public entities may not ask individuals using such devices about their disability but may ask for a credible assurance that the device is required because of a disability. If the person presents a valid, State-issued disability parking placard or card or a State-issued proof of disability, that must be accepted as credible assurance on its face. If the person does not have this documentation, but states verbally that the device is being used because of a mobility disability, that also must be accepted as credible assurance, unless the person is observed doing something that contradicts the assurance. For example, if a person is observed running and jumping, that may be evidence that contradicts the person’s assertion of a mobility disability. However, the fact that a person with a disability is able to walk for some distance does not necessarily contradict a verbal assurance – many people with mobility disabilities can walk, but need their mobility device for longer distances or uneven terrain. This is particularly true for people who lack stamina, have poor balance, or use mobility devices because of respiratory, cardiac, or neurological disabilities.

Communicating successfully is an essential part of providing service to the public. The ADA requires public entities to take the steps necessary to communicate effectively with people who have disabilities, and uses the term “auxiliary aids and services” to refer to readers, notetakers, sign language interpreters, assistive listening systems and devices, open and closed captioning, text telephones (TTYs), videophones, information provided in large print, Braille, audible, or electronic formats, and other tools for people who have communication disabilities. In addition, the regulations permit the use of newer technologies including real-time captioning (also known as computer-assisted real-time transcription, or CART) in which a transcriber types what is being said at a meeting or event into a computer that projects the words onto a screen; remote CART (which requires an audible feed and a data feed to an off-site transcriber); and video remote interpreting (VRI), a fee-based service that allows public entities that have video conferencing equipment to access a sign language interpreter off-site. Entities that choose to use VRI must comply with specific performance standards set out in the regulations.

Because the nature of communications differs from program to program, the rules allow for flexibility in determining effective communication solutions. The goal is to find a practical solution that fits the circumstances, taking into consideration the nature, length, and complexity of the communication as well as the person’s normal method(s) of communication. What is required to communicate effectively when a person is registering for classes at a public university is very different from what is required to communicate effectively in a court proceeding.

Some simple solutions work in relatively simple and straightforward situations. For example:

Other solutions may be needed where the information being communicated is more extensive or complex. For example:

Public entities are required to give primary consideration to the type of auxiliary aid or service requested by the person with the disability. They must honor that choice, unless they can demonstrate that another equally effective means of communication is available or that the aid or service requested would fundamentally alter the nature of the program, service, or activity or would result in undue financial and administrative burdens. If the choice expressed by the person with a disability would result in an undue burden or a fundamental alteration, the public entity still has an obligation to provide another aid or service that provides effective communication, if possible. The decision that a particular aid or service would result in an undue burden or fundamental alteration must be made by a high level official, no lower than a Department head, and must be accompanied by a written statement of the reasons for reaching that conclusion.

The telecommunications relay service (TRS), reached by calling 7-1-1, is a free nationwide network that uses communications assistants (also called CAs or relay operators) to serve as intermediaries between people who have hearing or speech disabilities who use a text telephone (TTY) or text messaging and people who use standard voice telephones. The communications assistant tells the voice telephone user what the TTY-user is typing and types to the TTY-user what the telephone user is saying. When a person who speaks with difficulty is using a voice telephone, the communications assistant listens and then verbalizes that person’s words to the other party. This is called speech-to-speech transliteration.

Video relay service (VRS) is a free, subscriber-based service for people who use sign language and have videophones, smart phones, or computers with video communication capabilities. For outgoing calls, the subscriber contacts the VRS interpreter, who places the call and serves as an intermediary between the subscriber and a person who uses a voice telephone. For incoming calls, the call is automatically routed to the subscriber through the VRS interpreter.

Staff who answer the telephone must accept and treat relay calls just like other calls. The communications assistant or interpreter will explain how the system works.

For additional information, including the performance standards for VRI, see ADA 2010 Revised Requirements: Effective Communication.

The ADA’s regulations and the ADA Standards for Accessible Design, originally published in 1991, set the minimum standard for what makes a facility accessible. Only elements that are built-in (fixed in place) are addressed in the Standards. While the updated 2010 Standards, which became effective on March 15, 2012, retain many of the original provisions in the 1991 Standards, there are some significant differences. The Standards are used when determining if a public entity’s programs or services are accessible under the ADA. However, they apply differently depending on whether the entity is providing access to programs or services in existing facilities or is altering an existing facility or building a new facility.

Public entities have an ongoing obligation to ensure that individuals with disabilities are not excluded from programs and services because facilities are unusable or inaccessible to them. There is no “grandfather clause” in the ADA that exempts older facilities. However, the law strikes a careful balance between increasing access for people with disabilities and recognizing the constraints many public entities face. It allows entities confronted with limited financial resources to improve accessibility without excessive expense.

In the years since the ADA took effect, public facilities have become increasingly accessible. In the event that changes still need to be made, there is flexibility in deciding how to meet this obligation – structural changes can be made to provide access, the program or service can be relocated to an accessible facility, or the program or service can be provided in an alternate manner. For example:

Whatever method is chosen, the public entity must ensure that people with disabilities have access to programs and services under the same terms and conditions as other people. For example:

There are limits to a public entity’s program access obligations. Entities are not required to take any action that would result in undue financial and administrative burdens. The decision that an action would result in an undue burden must be made by a high level official, no lower than a Department head, having budgetary authority and responsibility for making spending decisions, after considering all resources available for use in the funding and operation of the service, program, or activity, and must be accompanied by a written statement of the reasons for reaching that conclusion. If an action would result in an undue burden, a public entity must take any other action that would not result in an undue burden but would nevertheless ensure that individuals with disabilities receive the benefits or services provided by the public entity.

A key concept is that public programs and services, when viewed in their entirety, must be accessible to people with disabilities, but not all facilities must necessarily be made accessible. For example, if a city has multiple public swimming pools and limited resources, it can decide which pools to make accessible based on factors such as the geographic distribution of the sites, the availability of public transportation, the hours of operation, and the particular programs offered at each site so that the swimming program as a whole is accessible to and usable by people with disabilities.

Another key concept is that public entities have an ongoing obligation to make programs and services accessible to people with disabilities. This means that if many access improvements are needed, and there are insufficient resources to accomplish them in a single year, they can be spread out over time. It also means that rising or falling revenues can affect whether or not an access improvement can be completed in a given year. What might have been seen as an undue burden during an economic downturn could become possible when the economy improves and revenues increase. Thus, public entities should periodically reassess what steps they can take to make their programs and services accessible. Public entities should also consult with people with disabilities in setting priorities for achieving program access. See Planning for Success

Temporary access interruptions for maintenance, repair, or operational activities are permitted, but must be remedied as soon as possible and may not extend beyond a reasonable period of time. Staff must be prepared to assist individuals with disabilities during these interruptions. For example, if the accessible route to a biology lab is temporarily blocked by chairs from a classroom that is being cleaned, staff must be available to move the chairs so a student who uses a wheelchair can get to the lab. In addition, if an accessible feature such as an elevator breaks down, public entities must ensure that repairs are made promptly and that improper or inadequate maintenance does not cause repeated failures. Entities must also ensure that no new barriers are created that impede access by people with disabilities. For example, routinely storing a garbage bin or piling snow in accessible parking spaces makes them unusable and inaccessible to people with mobility disabilities.

For activities that take place infrequently, such as voting, temporary measures can be used to achieve access for individuals who have mobility disabilities. For more information, see Solutions for Five Common ADA Access Problems at Polling Places.

The requirements in the 2010 ADA Standards are, for many building elements, identical to the 1991 Standards and the earlier Uniform Federal Accessibility Standards (UFAS). For some elements, however, the requirements in the 2010 Standards have changed. For example:

If a facility was in compliance with the 1991 Standards or UFAS as of March 15, 2012, a public entity is not required to make changes to meet the 2010 Standards. This provision is referred to as the “safe harbor.” It applies on an element-by-element basis and remains in effect until a public entity decides to alter a facility for reasons other than the ADA. For example, if a public entity decides to restripe its parking lot (which is considered an alteration), it must then meet the ratio of van accessible spaces in the 2010 Standards. The ADA’s definition of the term “alteration” is discussed below.

The 2010 Standards also contain requirements for recreational facilities that were not addressed in the 1991 Standards or UFAS. These include swimming pools, play areas, exercise machines, court sport facilities, and boating and fishing piers. Because there were no previous accessibility standards for these types of facilities, the safe harbor does not apply. The program access rules apply, and the 2010 Standards must be followed when structural change is needed to achieve program access.

New Requirements in the 2010 Standards Not Subject to the Safe HarborWhen a public entity chooses to alter any of its facilities, the elements and spaces being altered must comply with the 2010 Standards. An alteration is defined as remodeling, renovating, rehabilitating, reconstructing, changing or rearranging structural parts or elements, changing or rearranging plan configuration of walls and full-height or other fixed partitions, or making other changes that affect (or could affect) the usability of the facility. Examples include restriping a parking lot, moving walls, moving a fixed ATM to another location, installing a new service counter or display shelves, changing a doorway entrance, or replacing fixtures, flooring or carpeting. Normal maintenance, reroofing, painting, wallpapering, or other changes that do not affect the usability of a facility are not considered alterations. The 2010 Standards set minimum accessibility requirements for alterations. In situations where strict compliance with the Standards is technically infeasible, the entity must comply to the maximum extent feasible. “Technically infeasible” is defined as something that has little likelihood of being accomplished because existing structural conditions would require removing or altering a load-bearing member that is an essential part of the structural frame; or because other existing physical or site constraints prohibit modifications or additions that comply fully with the Standards. The 2010 Standards also contain an exemption for certain alterations that would threaten or destroy the historic significance of an historic property.

The ADA requires that all new facilities built by public entities must be accessible to and usable by people with disabilities. The 2010 Standards set out the minimum accessibility requirements for newly constructed facilities.

2010 ADA Standards BasicsChapter 1: Application and Administration. This chapter contains important introductory and interpretive information, including definitions for key terms used in the 2010 Standards.

Chapter 2: Scoping. This chapter sets forth which elements, and how many of them, must be accessible.

Chapters 3 - 10: Design and Technical Requirements. These chapters provide design and technical specifications for elements, spaces, buildings, and facilities.

Common ProvisionsAccessible Routes – Section 206 and Chapter 4.

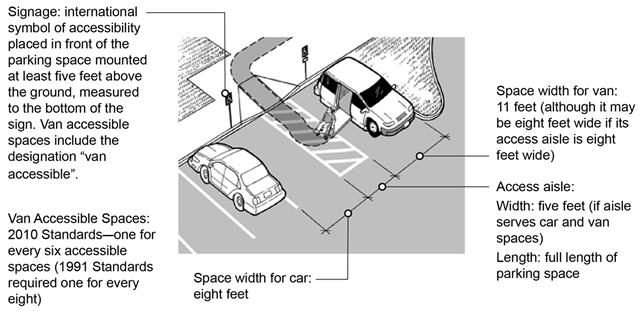

Parking Spaces – Sections 208 and 502. The provisions regarding accessible routes (section 206), signs (section 216), and, where applicable, valet parking (section 209) also apply.

Passenger Loading Zones – Sections 209 and 503.

Assembly Areas – Sections 221 and 802.

Sales and Service – Sections 227 and 904.

Dining and Work Surfaces – Sections 226 and 902. The provisions regarding accessible routes in section 206.2.5 (Restaurants and Cafeterias) also apply to dining surfaces.

Dressing, Fitting, and Locker Rooms – Sections 222 and 803.

The chart below indicates the number of accessible spaces required by the 2010 Standards. One out of every six accessible spaces must be van-accessible.

| Total Number of Parking Spaces Provided in Parking Facility | Minimum Number of Required Accessible Parking Spaces |

|---|---|

| 1 to 25 | 1 |

| 26 to 50 | 2 |

| 51 to 75 | 3 |

| 76 to 100 | 4 |

| 101 to 150 | 5 |

| 151 to 200 | 6 |

| 201 to 300 | 7 |

| 301 to 400 | 8 |

| 401 to 500 | 9 |

| 501 to 1000 | 2 percent of total |

| 1001 and over | 20, plus 1 for each 100, or fraction thereof, over 1000 |

Public entities with very limited parking (four or fewer spaces) must have one van-accessible parking space. However, no signage is required.

An accessible parking space must have an access aisle, which allows a person using a wheelchair or other mobility device to get in and out of the car or van. Accessible parking spaces (including access aisles) must be level (maximum slope 1:48 in all directions) and each access aisle must adjoin an accessible route.

One small step at an entrance can make it impossible for individuals using wheelchairs, walkers, canes, or other mobility devices to enter a public facility. Removing this barrier may be accomplished in a number of ways, such as installing a ramp or a lift or regrading the walkway to provide an accessible route. If the main entrance cannot be made accessible, an alternate accessible entrance can be used.

If there are several entrances and only one is accessible, a sign should be posted at the inaccessible entrances directing individuals to the accessible entrance. This entrance must be open whenever other public entrances are open.

The path a person with a disability takes to enter and move through a facility is called an “accessible route.” This route, which must be at least three feet wide, must remain accessible and not be blocked by items such as vending or ice machines, newspaper dispensers, furniture, filing cabinets, display racks, or potted plants. Similarly, accessible toilet stalls and accessible service counters must not be cluttered with materials or supplies. The accessible route should be the same, or be located in the same area as, the general route used by people without mobility disabilities.

The obligation to provide program access also applies to merchandise shelves, sales and service counters, and check-out aisles. Shelves used by the public must be on an accessible route with enough space to allow individuals using mobility devices to access merchandise or materials. However, shelves may be of any height since they are not subject to the ADA’s reach range requirements. A portion of sales and service counters must be accessible to people who use mobility devices. If a facility has check-out aisles, at least one must be usable by people with mobility disabilities, though more are required in larger venues.

Being proactive is the best way to ensure ADA compliance. Many public entities have adopted a general ADA nondiscrimination policy, a specific policy on service animals, a specific policy on effective communication, or specific policies on other ADA topics. Staff also need instructions about how to access the auxiliary aids and services needed to communicate with people who have vision, hearing, or speech disabilities. Public entities should also make staff aware of the free information resources for answers to ADA questions. And officials should be familiar with the 2010 Standards before undertaking any alterations or new construction projects. Training staff on the ADA, conducting periodic self-evaluations of the accessibility of the public entity’s policies, programs and facilities, and developing a transition plan to remove barriers are other proactive steps to ensure ADA compliance.

Public entities that have 50 or more employees are required to have a grievance procedure and to designate at least one responsible employee to coordinate ADA compliance. Although the law does not require the use of the term “ADA Coordinator,” it is commonly used by state and local governments across the country. The ADA Coordinator’s role is to coordinate the government entity’s efforts to comply with the ADA and investigate any complaints that the entity has violated the ADA. The Coordinator serves as the point of contact for individuals with disabilities to request auxiliary aids and services, policy modifications, and other accommodations or to file a complaint with the entity; for the general public to address ADA concerns; and often for other departments and employees of the public entity. The name, office address, and telephone number of the ADA Coordinator must be provided to all interested persons.

The 1991 ADA regulation required all public entities, regardless of size, to evaluate all of their services, policies, and practices and to modify any that did not meet ADA requirements. In addition, public entities with 50 or more employees were required to develop a transition plan detailing any structural changes that would be undertaken to achieve program access and specifying a time frame for their completion. Public entities were also required to provide an opportunity for interested individuals to participate in the self-evaluation and transition planning processes by submitting comments. While the 2010 regulation does not specifically require public entities to conduct a new self-evaluation or develop a new transition plan, they are encouraged to do so.

A critical, but often overlooked, component of ensuring success is comprehensive and ongoing staff training. Public entities may have good policies, but if front line staff or volunteers are not aware of them or do not know how to implement them, problems can arise.

It is important that staff – especially front line staff who routinely interact with the public – understand the requirements on modifying policies and practices, communicating with and assisting customers, accepting calls placed through the relay system, and identifying alternate ways to provide access to programs and services when necessary to accommodate individuals with a mobility disability. Many local disability organizations, including Centers for Independent Living, conduct ADA trainings in their communities. The Department of Justice or the National Network of ADA Centers can provide local contact information for these organizations.

For more information about the revised ADA regulations, the 2010 Standards, and the ADA, please visit ADA.gov or call our toll-free number.

ADA Information Line 800-514-0301 (Voice) and 1-833-610-1264 (TTY) M-W, F 9:30 a.m. – 12:00 p.m. and 3:00 p.m. - 5:30 p.m., Th 2:30 p.m. – 5:30 p.m. (Eastern Time) to speak with an ADA Specialist. Calls are confidential.

Ten regional centers are funded by the U.S. Department of Education to provide ADA technical assistance to businesses, States and localities, and people with disabilities. One toll-free number connects you to the center in your region:

For technical assistance on the ADA/ABA Guidelines:

This publication is available in alternate formats for people with disabilities.

The Americans with Disabilities Act authorizes the Department of Justice (the Department) to provide technical assistance to individuals and entities that have rights or responsibilities under the Act. This document provides informal guidance to assist you in understanding the ADA and the Department’s regulations.

This guidance document is not intended to be a final agency action, has no legally binding effect, and may be rescinded or modified in the Department’s complete discretion, in accordance with applicable laws. The Department’s guidance documents, including this guidance, do not establish legally enforceable responsibilities beyond what is required by the terms of the applicable statutes, regulations, or binding judicial precedent.

Duplication of this document is encouraged.

Originally issued: June 01, 2015

Last updated: February 28, 2020